GETTING OUT

Ronald Sanders in his book[1] about Jewish emigration refers to 1903-1909 as the ‘Era of Pogroms.' It was during this period, that Herschel Eisenberg left Telechan for the United States. "Getting Out" was not a simple task. Telechan is a village located far inland. Herschel needed to journey to a major seaport hundreds of miles away to cross the Atlantic Ocean. This, in turn, necessitated travel through several different countries. Due west of Russia was Poland and then Germany. After Germany came the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, all countries from which many Atlantic crossings originated.

Herschel departed from Antwerp, Belgium, the same year that a man named Alexander Harkairy, representing both a HIAS (Hebrew Immigration Aid Society) and Ellis Island, traveled to Europe to view first hand the situation of prospective immigrants. Harkairy left New York in November, just four months after Herschel traveled in the opposite direction. Herschel almost certainly experienced the conditions described by Harkairy who interviewed emigrants in transit.

"In general they (emigrants) must avoid Germany which does not pass persons intending to go by (ship) lines other than German." That meant that emigrants needed to ‘make a long route...’ through Austria, to Switzerland and on to Antwerp, Belgium or Rotterdam, Netherlands. This required traveling through France. It was indeed a long journey.

The majority of people who emigrated from what was then Tsarist Russia made their way by special trains across Europe to one of many Western European ports. The train ride was included in the price of the steamship ticket. That experience itself could be very difficult, sometimes taking up to several weeks.

In Belgium, Harkairy traveled to Antwerp, which was a major transit point for Jewish emigrants from Poland, Russia, and other East and Central European communities. Usually they were waiting for permission to enter the US. Harkairy visited the Red Star Line office; the very ship line that Herschel took and other Eisenbergs were to take on their trans-Atlantic trips to the United States.

Harkairy found that Antwerp "as a port of embarkation for emigrants proved to have problems." "Conditions in the emigrant hotels were poor." The port side hotels provided dormitory style lodgings for the average stay of four days during which time prospective passengers were deloused, twice. The local Hias assumed some responsibility for clothing, feeding and housing the transit immigrants. Once aboard the ships there were no kosher facilities. This presented a major problem for passengers who observed kashruth.

Fifteen years later, Dov Berel, Elka, Leja and Mowsza came to the United States embarking from Antwerp, aboard the Red Star Line ships, SS Gothland and SS Finland. Presumably conditions had improved. Did they too, take the long route to get to Antwerp, deal with poor hotels and non-kosher food on board?

The port of departure had little or no bearing to where passengers lived. Most immigrants did not care where they left from as long as they got out and ended up in the US. It was an issue of supply and demand for steamship tickets. Passage in steerage was ‘first come, first served’. In the 1900s the ticket was not for a specific ship, it was simply for passage to America with a particular steamship company. Transporting emigrants was a very profitable and competitive business.

At times, there were price wars between various steamship lines. Independent agents, working on commission, peddled tickets from shtetl to shtetl. Although Ajzenbergs left Telechan over a period of fifteen years, they all traveled to the US via Antwerp and the Red Star Lines. Apparently a salesman for The Red Star Lines included Telechan in his territory.

During the 1920s a child’s (age 7-10) fare on The Red Star Line was half of the regular adult fare ($65.00 versus $130.00). This, no doubt, accounts for the fact that my father is listed as 9 years old on all ship documents. By every other account he was 13 years old when he immigrated.

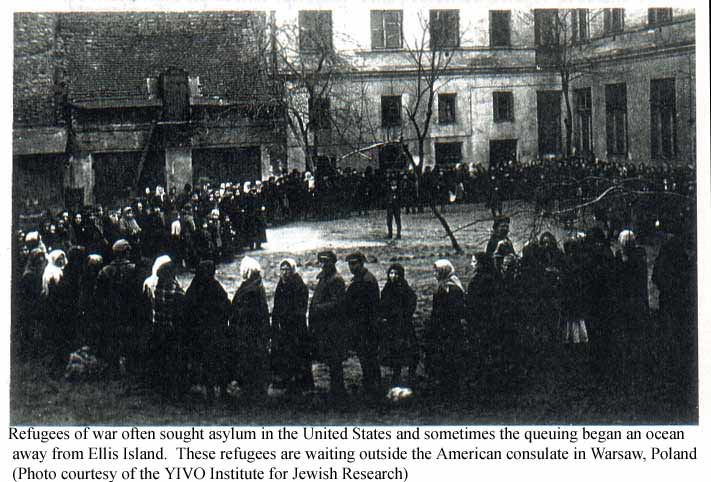

How did they ‘Get Out’? The passport application process was complicated. The US State Department required all prospective immigrants to obtain their visas from an American Consul in the country to which they owed allegiance. To get a visa, one must first obtain a passport. In the 1920s Telechan was in the Republic of Poland, therefore my relatives needed to obtain visas from the U.S. Consul there. Somehow they accomplished that.

Dov Berel, Elka, Leja, and my father were lucky. "...owing to the extraordinary conditions that prevailed, a large number of emigrants, among them women and children, could not possibly remain in Poland until the Polish Government issued passports to them. They went to France, Holland, and Belgium, minus passports, and successfully obtained passports from the Polish Consul in these countries. Difficulties arose when the emigrants applied to the American Consul for visas. They were told to return to Poland and have their passports visa by the American Consul there.” That was impossible. A "Catch 22.” Somehow, my family overcame that problem.

There is some documentation available regarding Dov Berel and the others obtaining visas and passports. The Polish Government issued Dov Berel’s passport on March 9, 1921, in Warsaw, which is over 200 miles west of Telechan. The American Consul in Warsaw issued his visa more than four months later on July 27, 1921. Elka, Leja, and Mowsza did not obtain their documentation at the same time as Dov Berel. Their Polish passports were issued in Luninca, Poland on July 20, 1921, four months after Dov Berel received his. I believe Luninca is also known as Luninets, a city only 44 miles southeast of Telechan. Luninets was the home of Motol and Chana Eizenberg. Motol was Dov Berel and Elka’s middle child of their seven children. At the time, Motol and Chana had one child, Rose (Eizenberg) Barr, then five years old. Rose recalls that the four travelers (Dov Berel, Elka, Leja, and Mowsza) ‘went past our house on the way to America’ and that ‘they stayed with us in Luninets for one or two nights.’ Rose remembers ‘Elka walking into the room’ in her house before she left for America. ‘They stayed with us because it was on the way to Warsaw.'[2] Presumably, Warsaw was the starting point for the westward journey across Europe.

The record shows that Elka, Leja, and Mowsza received their visas[3] from the American Consul at Warsaw on July 28, 1921, one day after Dov Berel obtained his and only one week after getting their passports. It appears that Dov Berel was the advance guard in this document-procuring endeavor. He made the initial attempts to acquire the appropriate documents. The others then followed.

WHY THEY LEFT

Referring to the disastrous effects of World War I, Colonel W.R. Grove of the American Relief Administration wrote:

"It is doubtful if in any of the devastated areas of the war there is as much human suffering as exists along that great stretch between Congress Poland and the Bolshevist line."[4] (Shores of Refuge, Ronald Sanders, p. 368)

In 1919 and 1920 European distress was greatest in the areas where Jews were most thickly settled. An American-Jewish relief organization working in the area reported that for

"the small towns in the Pinsk district "...

"the situation"...was "quite impossible."

A town, for example, like the town of TELECHANY

is entirely destroyed, people are living in trenches."[5]

This reference to Telechan is the only one I have ever seen apart from the Telechan Memorial Book itself.

This was the Telechan of the Ajzenberg family just before Dov Berel, Elka, Leja and Mowsza came to the United States. Hunger and starvation were widespread. "Refuges from Eastern Poland"...began "to flock into Warsaw by the thousands."[6] My father was one of those refugees.

WHERE TO GO??

"Getting out" was the first half of the equation. "Where to go" became the next problem. The following two humorous stories capture the difficulty that now needed to be confronted. Although these anecdotes refer to the Nazi era, they highlight similar problems' immigrants encountered in an earlier time.